Kurdish Deq is the Power of Seven

Dr Rebwar Fatah

“The symbol reflects a traditional Kurdish facial tattoo motif associated with protection, light, and continuity, drawing on ancient regional cosmological imagery rather than formal religious doctrine. It belongs to folk heritage, not ideology.”

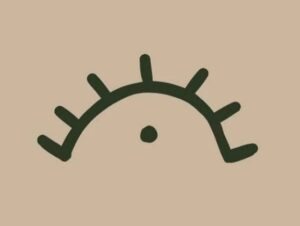

A small mark on the brow can carry a continent of meaning. The motif is spare — a curved arch like a horizon, a single dot beneath it, and seven short rays rising above — yet when placed on a forehead it reads as a compact grammar of protection, lineage, and cosmology. This design belongs to the Kurdish deq or xal tradition of facial marks historically worn by women across northern Syria (Rojava), Kurdistan Region-Turkey (southeastern Turkey), Kurdistan Region-Iraq (northern Iraq), and Kurdistan Region _Iran (western Iran). It is not a doctrinal emblem but a folk sign whose meanings overlap and accumulate: solar imagery, a watching eye, the symbolic power of seven, and a marker of feminine continuity.

Solar Light and the Protective Vault

At its most immediate level the arch, dot, and rays evoke a rising sun. The arch functions as horizon or protective vault; the dot beneath it can be read as a seed, a soul, or an eye; the rays are light, vitality, and renewal. Solar imagery in Mesopotamia and the Kurdish cultural sphere is ancient and persistent, surviving in folk practice rather than formal theology. Placed on the forehead — the most visible and symbolically “open” part of the body — the mark becomes a visible invocation of life and continuity, a small cosmology worn on the face.

The Watching Eye and Anchoring the Soul

In oral traditions the dot beneath the arch is often interpreted as an eye, a talismanic mark that sees and is seen. As a protective sign it is meant to guard against envy, illness, and misfortune; as an anchor it secures identity and the soul’s presence in the world. These marks were not applied casually. They were ritualized, transmitted within families, and understood as practical spiritual technology: a visible safeguard for a life lived in precarious times. The forehead placement amplifies the mark’s function as a public, social protection — a declaration that the wearer is watched over and anchored to a lineage.

Seven as Cosmic Order

The seven rays are not incidental. Across Kurdish, Iranian, and broader

Mesopotamian traditions the number seven carries dense symbolic freight: completeness, cosmic order, and continuity across generations. Linguistically and culturally the Kurdish terms for seven and the week — heft, hefte, or hafta — tie the number to calendrical cycles and social rhythms. The Kurdish name Hewtewane maps directly onto a stellar reality: the Big Dipper or the Plough, a seven star grouping within Ursa Major used in navigation and seasonal reckoning. That celestial association reinforces the motif’s cosmological resonance: the forehead mark is a microcosm of sky and time, a terrestrial echo of a stellar pattern that guided farmers, shepherds, and travelers.

Feminine Identity, Transmission, and Revival

Historically these facial marks were predominantly female marks, transmitted mother to daughter. They signified belonging, fertility, endurance, and social identity rather than doctrinal faith. In many communities the deq was a rite of passage, a visible lineage marker that encoded family history and local belonging. The practice anchored women to kinship networks and to the land, and it functioned as a living archive of communal memory. In contexts where identity was contested or threatened, the deq served as a quiet but durable assertion of continuity.

What is new is not the symbol but its revival. In recent demonstrations worldwide in solidarity with Rojava — the HDS controlled region in northeast Syria — young women have begun to wear the same forehead motif. Observers who had not seen the mark in public for decades now report it appearing in protest squares, on social media, and at cultural gatherings. The reappearance feels like a cultural echo: an ancient sign reactivated by contemporary urgency. When young girls draw that arch, dot, and seven rays on their brows, they are not merely adopting a fashion; they are reviving a lineage, making visible a continuity that political violence and displacement tried to erase.

From Folk Mark to Political Symbol

The revival transforms a private, familial practice into a public, political language. In protest contexts the mark becomes a visible claim of identity and solidarity; it signals that cultural memory matters in political life. The forehead motif now functions on two registers at once: as a reclaimed heritage and as a deliberate act of resistance. For displaced communities and diasporas, re inking the deq is a way to assert presence in a world that often reduces people to statistics and borders.

This shift also changes how the symbol is read by outsiders. What once might have been dismissed as quaint or archaic now carries contemporary urgency. The mark’s ancient cosmology lends moral weight; its modern visibility gives it political force. Young women who wear it in demonstrations are saying that their culture is not a relic but a living resource for dignity and resistance.

Distinctions and Careful Reading

Two common confusions deserve correction. First, the deq is cosmological and protective, not a confession of religious doctrine; calling it “pagan” flattens its social and historical function. Second, do not conflate Hewtewane with the Pleiades. The Big Dipper (Hewtewane) is a distinct seven star grouping used in navigation and seasonal reckoning; the Pleiades — the “Seven Sisters” — are a different cluster with their own names and stories in Kurdish lore. Precision matters because local lexical terms encode specific practices and seasonal knowledge.

Why the Mark Matters Now

A forehead motif — arch, dot, seven rays — is a small visual grammar that carries a long cultural sentence. It links forehead to horizon, family to cosmos, and memory to political presence. In an era of displacement and cultural erasure, the reappearance of these marks is an act of reclamation: a way to say that identity is not negotiable, that history is not disposable, and that the sky’s memory still has a place on the human face. For readers who encounter the symbol in a photograph or on the street, it is worth pausing: beneath the simple geometry lies a layered history of protection, belonging, and the stubborn human desire to be seen.