The Kurdish Question as a Legal–Political Failure: Selective Humanitarianism and the Erosion of International Law

Dr Rebwar Fatah

Abstract

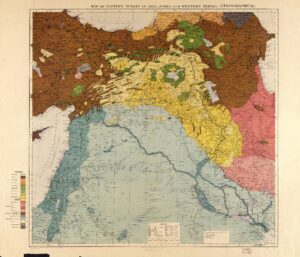

This article examines patterns of external engagement with Kurdish populations in the Middle East through the lens of international humanitarian law and international criminal law. Drawing on historical and contemporary examples from Iraq, Iran, Turkey, and Syria, it analyses how Kurdish displacement and insecurity have recurrently been framed in humanitarian terms while the underlying legal implications of occupation, forced displacement, demographic change, and accountability have remained underexamined. The article evaluates relevant legal frameworks, including the law of occupation, prohibitions on population transfer and property appropriation, and the elements of crimes against humanity, with particular attention to questions of foreseeability, preventability, and capacity to influence. Without attributing legal responsibility to specific actors, it argues that the substitution of humanitarian management for legal accountability has contributed to cyclical instability and weakened the preventive function of international criminal law. The article concludes that sustained marginalisation of legal analysis in the Kurdish context risks further erosion of international legal norms and undermines long-term civilian protection.

External engagement with the Kurdish question has long exhibited a pattern that raises serious legal as well as political concerns. Kurdish populations are frequently reduced to variables of territory, casualty figures, and humanitarian need, while international actors invoke moral responsibility selectively—often after large-scale harm has occurred, and frequently without assuming responsibility for the structural conditions that enabled such harm (UNSC, 2021, paras. 3–5). This mode of engagement risks transforming humanitarian concern into a substitute for political and legal accountability.

The Kurdish situation cannot be accurately characterised as a series of isolated humanitarian crises. Rather, it reflects a recurring historical condition in which Kurdish communities, across multiple states, have been subjected to repression, forced displacement, and mass violence in ways that engage core principles of international law. Episodes in Iraq (including 1975 and the 1990s), Iran (post-1979), Turkey (particularly during the 1980s and 1990s), and more recently Syria, demonstrate a persistent pattern of vulnerability arising from the denial of political representation, protection, and meaningful self-governance (UN Special Rapporteur on Minority Issues, 2010, paras. 12–18). These episodes are not merely tragic events; they constitute a structural failure to uphold obligations related to minority protection, civilian protection during armed conflict, and, in some instances, the prohibition of crimes against humanity.

International responses to these situations have often been framed narrowly in humanitarian terms, emphasising emergency relief, civilian casualties, or displacement figures, while avoiding engagement with the underlying legal dimensions of responsibility. Such approaches risk depoliticising violations that implicate binding legal norms. Under international humanitarian law, the protection of civilian populations is not discretionary. Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions prohibits violence to life and person, cruel treatment, and outrages upon personal dignity against civilians (Geneva Conventions, 1949, Common Art. 3). Additional Protocol I further prohibits attacks against civilians and civilian objects and forbids collective punishment (AP I, Arts. 51–52).

Where patterns of conduct involve forcible displacement, persecution, or other inhumane acts committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against a civilian population, they may engage the prohibition of crimes against humanity under customary international law and Article 7 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (Rome Statute, 1998, Art. 7(1)(d), (h); ICC, Elements of Crimes, 2011).

The situation in Afrin illustrates these concerns. Reports of large-scale displacement of the indigenous population, confiscation of property—including olive groves—and interference with cultural heritage raise serious questions under the law of occupation (UN OHCHR, 2020, paras. 57–64). Under the Fourth Geneva Convention, an occupying power must respect private property and is prohibited from carrying out individual or mass forcible transfers of protected persons (GC IV, Arts. 49, 53). Article 8(2)(a)(iv) of the Rome Statute further criminalises extensive destruction and appropriation of property not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly (Rome Statute, Art. 8(2)(a)(iv)).

Where demographic change is pursued through coercive displacement or settlement practices, such conduct may also implicate the prohibition on population transfer under international humanitarian law (GC IV, Art. 49(6)) and has been recognised in international jurisprudence as a potential component of crimes against humanity where carried out in a systematic manner (ICTY, Stakić, Judgment, para. 679).

In this context, Kurdish armed self-defence has often been portrayed as a destabilising factor, detached from the conditions that gave rise to it. From a legal perspective, however, the emergence of non-state armed groups must be understood within environments characterised by chronic protection deficits. While international law does not legitimise violence per se, it places primary responsibility for civilian protection on states and, where applicable, occupying powers (ICRC, Customary IHL Study, Rule 1). Persistent failures to discharge these obligations contribute to cycles of insecurity that are then cited to justify further intervention or disengagement (UNSC, 2022, paras. 28–30).

Importantly, Kurdish claims are not limited to moral appeals. They are grounded in legal principles including the right of peoples to self-determination (UN Charter, Art. 1(2); ICCPR, Art. 1), the prohibition of discrimination (ICCPR, Art. 26), and protections afforded to minorities under international law (ICCPR, Art. 27). While self-determination does not automatically entail statehood, international law recognises internal self-determination, encompassing meaningful political participation, cultural autonomy, and protection from coercive demographic practices (UN General Assembly, Declaration on Friendly Relations, 1970).

The persistence of this pattern is facilitated by selective memory and rhetorical framing. Political assurances are offered without legal codification, and expectations are fostered without corresponding guarantees. Yet international law does not permit the instrumentalisation of civilian suffering for strategic gain, nor does it excuse inaction in the face of foreseeable harm (UN Secretary-General, Rights Up Front, 2013).

After decades of repeated violence, displacement, and instability, the region has not achieved greater security. This outcome reflects not the failure of Kurdish communities, but the cumulative effect of decisions taken by actors with power, influence, and legal obligations. When violations of international law are addressed through rhetoric rather than accountability, both morality and law are weakened. Where crimes against humanity risk becoming routine, the credibility of the international legal order itself is placed in question (UNSC, 2023, paras. 3–4).

Selected References (Harvard Style)

Geneva Conventions (1949), Common Article 3; Fourth Geneva Convention, Arts. 49, 53.

Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions (1977), Arts. 51–52.

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (1998), Arts. 7, 8.

ICC (2011), Elements of Crimes, International Criminal Court.

ICTY (2003), Prosecutor v. Stakić, Trial Judgment.

ICRC (2005), Customary International Humanitarian Law Study, Rules 1, 129.

UNSC (2021), Report of the Secretary-General on the threat posed by ISIL (Da’esh), S/2021/XYZ.

UNSC (2022), Report of the Secretary-General on the threat posed by ISIL (Da’esh), S/2022/XYZ.

UNSC (2023), Report of the Secretary-General on the threat posed by ISIL (Da’esh), S/2023/XYZ.

UN OHCHR (2020), Report on the Human Rights Situation in Afrin, paras. 57–64.

UN GA (1970), Declaration on Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations.

UN Secretary-General (2013), Rights Up Front Initiative.

ICCPR (1966), Arts. 1, 26, 27.