Unveiling the Unheard Truths of Anfal: A Deep Dive into Complicity, Silence, and Forgotten Justice

Wrya Abudlkhaliq

Introduction

The Anfal genocide, perpetrated by Saddam Hussein’s regime in the late 1980s, remains one of the most horrifying and painful episodes in Kurdish history. With the murder of more than 180,000 Kurdish civilians, the campaign was marked by chemical attacks, mass executions, forced disappearances, and village destructions. While the world largely recognizes the brutality of the Ba’ath regime, the internal Kurdish dynamics that followed the 1991 uprising—and the subsequent decisions by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG)—have remained cloaked in silence, denial, and political accommodation.

Through this report, based on extensive investigative journalism for Bowar News and rooted in my personal identity as the son of an Anfal victim, I aim to bring forth key documents and little-known facts that have either been ignored or deliberately buried. This article is not just a historical recount but a demand for truth, justice, and transparency.

Government Justifications for Inaction: A Shield for Collaborators

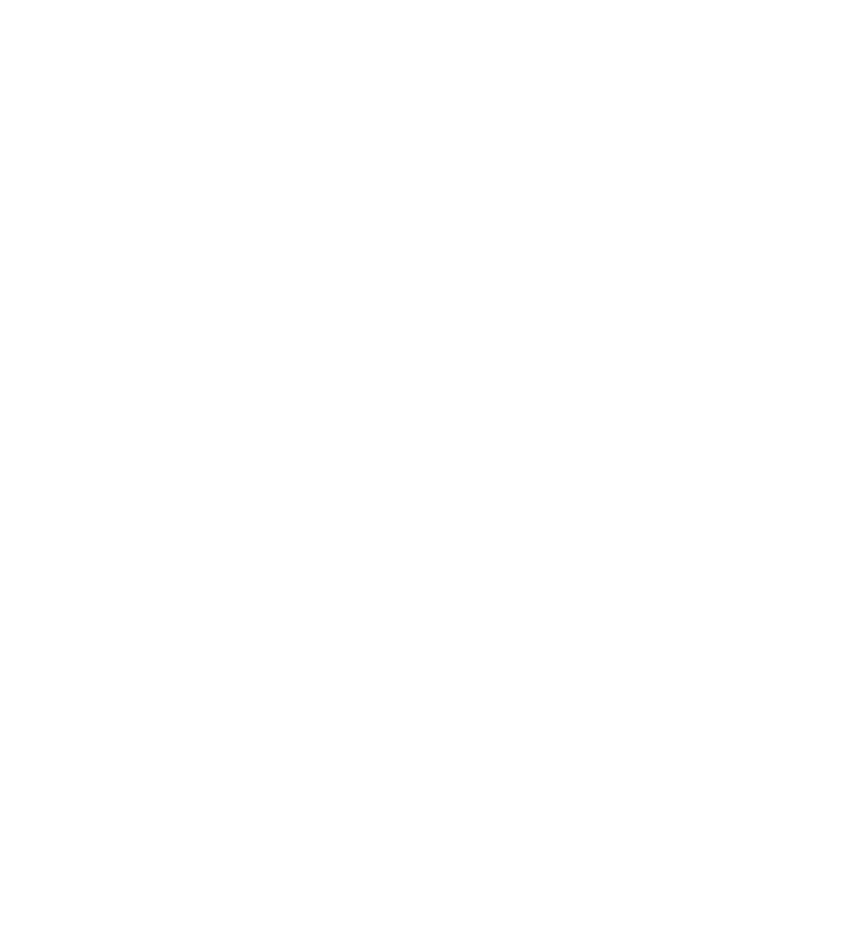

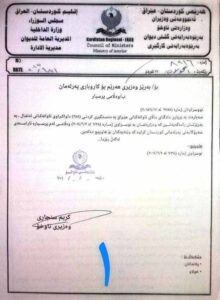

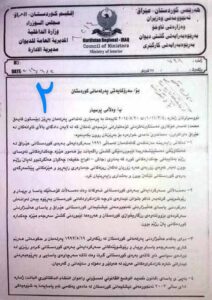

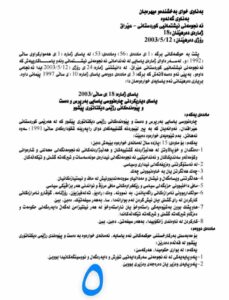

Perhaps the most shocking revelations come from internal documents issued by the Ministry of Interior of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), which openly explain why jash (Kurdish collaborators) and regime advisors involved in Anfal have not been arrested or prosecuted. These justifications, cataloged as Documents 1, 2, and 3, detail the political rationale for allowing these individuals to walk free.

The documents argue that pursuing these suspects would threaten “national unity” and destabilize the fragile post-uprising political order. They frame justice as a secondary concern, subordinate to the interests of political consolidation and internal peace.

Welcoming the Perpetrators: Barzani and Talabani’s Visit to a Jash Leader

Historical memory must not overlook that in the first week of the 1991 Kurdish uprising, Massoud Barzani (KDP leader) and Jalal Talabani (PUK secretary) were hosted by Hussein Agha Surchi, one of the most infamous and powerful jash commanders in Kurdistan. This visit documented and confirmed by multiple sources symbolized a quiet but powerful message: even those involved in genocide could find rehabilitation if they held political utility.

This same pattern manifested in the deal where the Kurdistan Front sold equipment from the Bekhma Dam project to Omar Agha Surchi, commander of the 77th Jash Battalion, for two million Swiss dinars. This wasn’t just a sale it was a transaction between political actors and war-time collaborators.

Jash and Advisors Recycled into Politics

After the uprising, many jash and regime collaborators were not only forgiven but absorbed into the very political system they once helped to destroy. The distribution of these individuals across party lines is stark:

- 168 battalion chiefs and advisors joined the KDP

- 65 joined the PUK

- 9 later joined Gorran

- 4 were absorbed into the Conservative Party

- 1 joined the Communist Party

- The Socialist Party initially received a regiment commander who later moved to the KDP

- Another commander joined the Yazidi Reform and Progress Movement

This broad spectrum participation reflects a deep moral compromise: that Kurdish autonomy and political power were built in part on the backs of those who had once helped destroy Kurdish communities.

Voices from the Darkness: Letters from Victims and Survivors

Among the few surviving traces of those who perished in Anfal is a deeply emotional letter written by Osman Hassan Faraj from Golbakhi village, addressed to his brother Omar. Dated before his disappearance, the letter is a haunting reminder of the humanity that was extinguished. Document 4.

Legalized Amnesty: Law No. 18 of 2003

In the immediate days following the uprising, the Kurdistan Front issued an amnesty for all jash and advisors involved in Anfal and other crimes. This sweeping gesture was soon enshrined into law. In 2003, the Kurdistan Parliament passed Law No. 18, confirming the amnesty decision. Article 1 explicitly refers to the Kurdistan Front’s earlier ruling, granting impunity to those who participated in the regime’s crimes.

This law has remained untouched, a testament to how political necessity has continually outweighed justice for victims. doc 5

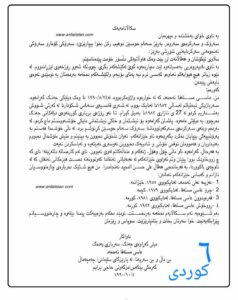

Even more unique is the case of Aasi Mustafa Ahmad, a resident of Zeinane Sangaw, who was the only Kurdish citizen known to have written directly to Saddam Hussein about Anfal. Captured during the Iran-Iraq war in 1982 and released in 1990, Aasi returned to find his wife and three children gone. His courageous letter, along with Saddam’s response, was translated and published by Anfalstan magazine (Documents 6 & 7).

Anfal as a Place Name: Institutionalizing Genocide

In a chilling act of normalization, Saddam Hussein in 1988 renamed the Kormor oil field as Anfal Field, a name that persisted until 2003. Even today, some documents and maps produced by the Northern Oil Company and Iraq’s Ministry of Oil still label the location as ANFAL (Figure 8). This transformation of genocide into geography reveals the depth of the regime’s ideological imprint.

Governmental Absence and Indifference

Despite the gravity of Anfal, the Minister of Martyrs and Anfal Victims Affairs of the KRG has not participated in the official Anfal anniversary ceremonies for three consecutive years. Even more disgracefully, the Minister was absent during the return of more than 170 victims’ bodies to Chamchamal, while two Iraqi government ministers, including a Christian, attended in solidarity.

This level of absence speaks volumes about the political marginalization of Anfal victims in contemporary Kurdish governance.

The Geography of Memory: Garmian as the Sole Commemoration Zone

Official KRG documents designate April 14 as the anniversary of the Anfal genocide only in Garmian, and specifically within Chamchamal and Kalar. (Document 9) This narrow geographic framing excludes victims from other areas, reducing the scope of commemoration and reinforcing a selective memory policy that benefits current political narratives.

The Largest Anfal Grave: Discovered But Unclaimed

Recently, the largest known mass grave of Anfal victims was unearthed in Kirkuk, containing the remains of approximately 2,100 individuals. The site had served as a municipal cemetery during the Ba’ath regime and continued to be used until 2003.

Despite its importance, neither the KRG nor the Ministry of Martyrs and Anfal Victims Affairs have claimed responsibility or shown initiative in this discovery. This silence further exposes the disconnect between state institutions and the victims they are meant to represent (Document 10).

Legal Intimidation: Silencing Journalists and Victims’ Families

As a journalist and as the son of an Anfal victim, I have not been immune to retaliation. I have been summoned before both a judge and a court in response to complaints filed by the families of two former jash leaders. This legal harassment is part of a broader pattern of silencing those who dare to question official narratives or expose uncomfortable truths.

Conclusion

The Anfal campaign did not end with Saddam Hussein. Its legacy continues in the silence, the selective memory, and the impunity granted to those who collaborated with tyranny.

This investigation is not merely a recount of historical facts it is a testimony, a resistance, and a demand.

As the son of an Anfal victim, I owe it to the past to speak these truths.

We must recognize that justice delayed by political convenience is justice denied. And only through collective reckoning can we begin to heal the wounds left by genocide.

Author Profile

- Diyar Harki is an independent investigative journalist and human rights advocate. As a member of the National Union of Journalists (NUJ), he focuses on exposing corruption and human rights abuses in Kurdistan and Iraq. He voluntarily contributes to Kurdfile Media.

Kurdistan18 January 2026Will the Terrorists Be Released?

Kurdistan18 January 2026Will the Terrorists Be Released? Opinion17 January 2026A Risk That Could Reshape the Kurdistan Region

Opinion17 January 2026A Risk That Could Reshape the Kurdistan Region Reports7 January 2026Kurdistan MPs Receive Millions in Salaries as Parliament Remains Paralyzed

Reports7 January 2026Kurdistan MPs Receive Millions in Salaries as Parliament Remains Paralyzed Political3 January 202634% of Kurdish MPs in Iraqi Parliament Lack Arabic Proficiency

Political3 January 202634% of Kurdish MPs in Iraqi Parliament Lack Arabic Proficiency